An introduction to Madhyasthal's DCE pass

Madhyasthal is the Bali JavaScript engine's midtier JIT compiler.

"Madhyasthal" in Hindi quite literally means "middle place" or "middle ground", indicating that it's supposed to provide a mix between the baseline JIT's fast compilation times and the (future) aggressive JIT's code quality. It uses a two-address code intermediate representation internally called, very creatively, MIR or Madhyasthal intermediate representation.

The IR

Madhyasthal uses a two-address code IR which is very similar to the engine's original bytecode format. An Instruction can only accept two arguments at most.

An argument can be:

- a signed integer

- a virtual register index

- a string

- a float

Why a two-address code IR?

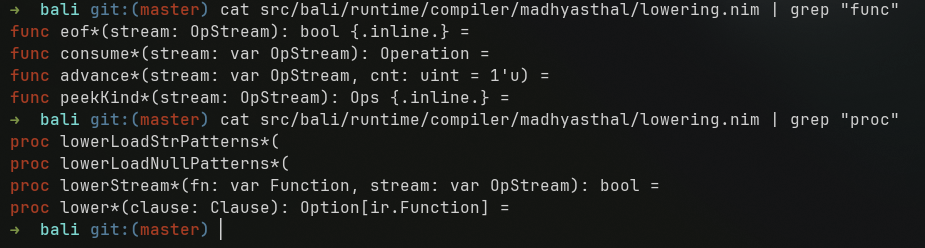

Mostly because I'm lazy. Also, the bytecode itself is a two-address code, so the lowering mechanism for bytecode to Madhyasthal IR is very simple: it's a simple stream reader that either matches and combines various bytecode opcode patterns into one special Madhyasthal opcode, or translates each one into its Madhyasthal equivalent if no such pattern can be observed.

The DCE pass

This is the very first optimization pass that was ever introduced into Madhyasthal. I call it a "naive dead code eliminator" because it was made using basic logical inference, and not any tried-and-tested methods. Again, I have no formal education in compilers (yet, mostly because I'm still in school), so cut me some slack. :^)

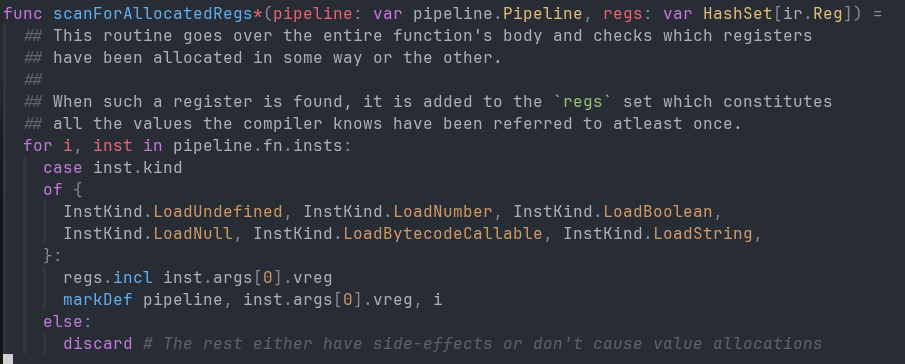

Step 1: Collect all defined ("allocated") registers

This is a very simple step. It basically tries to find all instructions that can define/allocate a value at a virtual register index.

Step 2: Collect all used registers

This is where the real action takes place. The code is too large to fit in one screenshot, so I'll just explain it as thoroughly as I can:

The instructions that can be considered to be uses are:

- Passing an argument to a function

- Invoking a function callable from that virtual register (or attempting to, atleast)

- Arithmetic operations

- Copying the virtual register to another

- Returning the virtual register

The first two are fairly mundane. Let's look at the third one.

Eliminating Arithmetic Operations

Arithmetic operations are treated specially here, since they take in [A] and [B] and store their result in [A].

What we can do is perform a lookahead and check whether [A] is used ahead in any operations. If it isn't, we can safely eliminate the arithmetic operation. Otherwise, we need to let it survive.

A scan-ahead will cause the callee to prematurely terminate and append the scan's result to the final output set. This optimization prevents wasteful duplicate scans from continuing further, which can cause multiple-second hangs in certain denser programs.

A similar approach is used to Copy instructions.

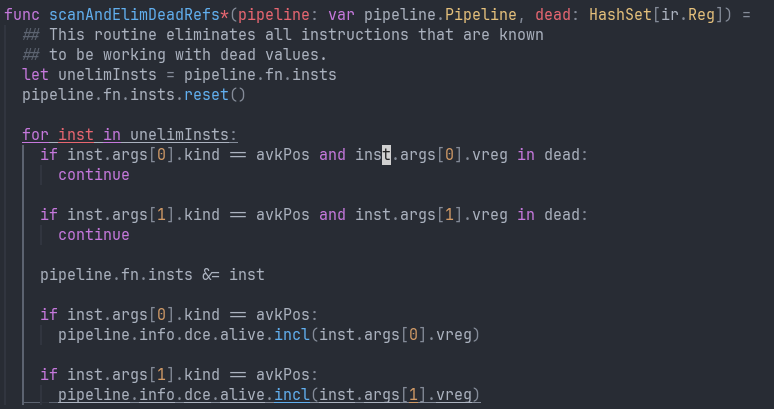

Step 3: Rewrite the instruction list

Now that we know which registers are dead, we can iterate over all instructions. If an instruction take in any registers marked as dead, we can safely eliminate it.

Step 4: Profit

Voila, you can now eliminate unused expressions fairly well. The best part? This is only 150 lines of code.

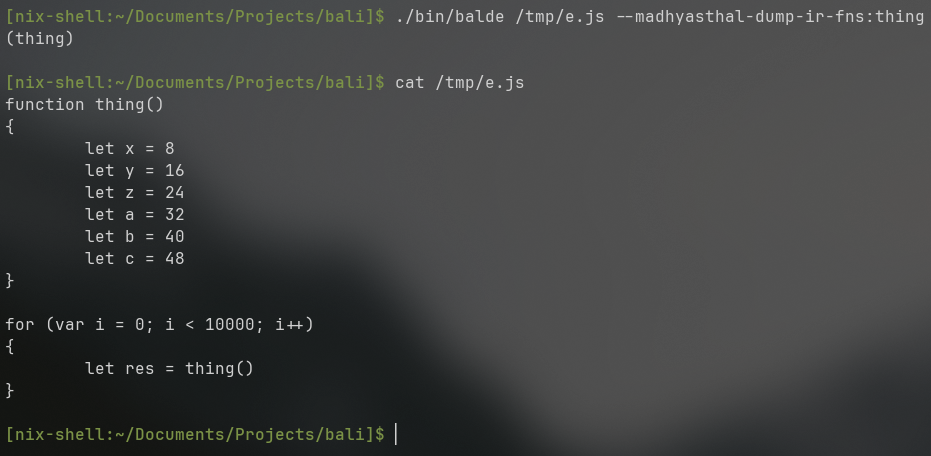

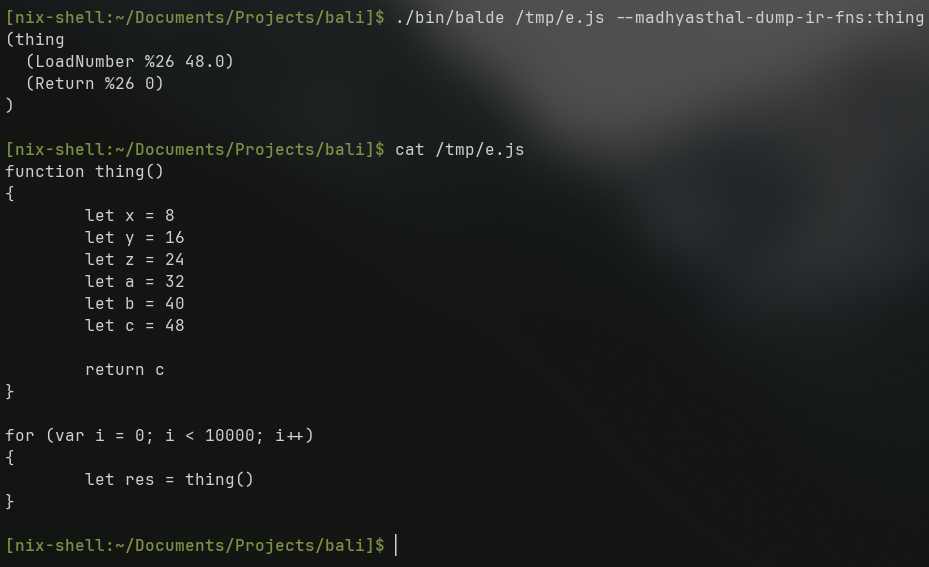

The below image shows you how the thing() function was fully optimized out, since nothing in it was used.

However, if one of the inputs is used, it is marked as alive and code for it is generated, as seen in the image below.

Closing Notes

This algorithm was fairly fun to create. If you have any recommendations, feel free to let me know. I'd love to improve this further into a lean fully-fledged DCE pass. I generally don't check my e-mail, though.